Appreciating Our Modern Kitchens

From your email, please click on the title to view the photos and comment online.

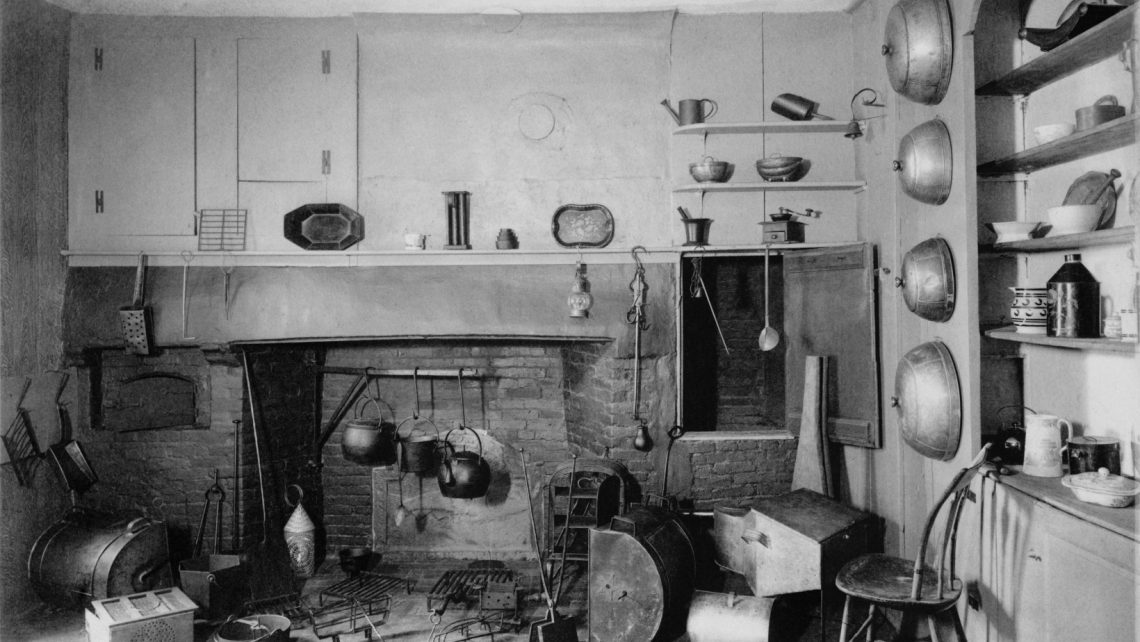

Thank heavens for labor-saving devices. These days, it’s not just the coffee maker and the Instant Pot and the slow-cooker; let’s not forget the refrigerator and the stove. I just finished reading The Kitchen in History by Molly Harrison and America’s Kitchens, published by Historic New England. This look at kitchens through the ages gave me a whole new appreciation for our modern gadgets as well as the appliances standard today. My everlasting impression is the amount of time that was spent in the 17th century to feed the family. As we celebrate the bravery of our forebears this July 4th weekend, let’s reflect on what they had to do to get dinner on the table.

Staying alive

The folks who settled the Americas in the 1600s spent most of their time just trying to stay alive, when you think about it. Cooking took place over a large hearth using the few pots and utensils that the family owned. That meant that the men spent a lot of time tending the cattle, pigs, sheep, and chickens and growing the grain and hay to feed them. They also needed to gather, cut to size, and split a remarkable amount of wood to fuel the fires. At harvest, they needed to cut, dry, and thresh the grain. Grain for consumption had to be milled.

Life for the woman of the house was no easier. Refrigeration and canning were not yet dreamed of, and families ate a lot of salt meat – if you could get sufficient salt. “Pioneer wives struggling to raise families in the wilderness, gritted their teeth, rolled up their sleeves, and probably cooked everything from buffalo tongue to beaver tail… Once settled on farms, they were busy from dawn to dusk and bought nothing that could be raised, grown, or cooked at home.”

Dining took place in the main room of the house with families seated on simple stools or benches. Trenchers (the dinner plates of the era) were made of wood and often spoken of as having a dinner side and a pie side. Two people often ate from the same dish, and a couple sharing a trencher were considered to be betrothed. And let’s remember that any water used for the livestock or other purposes had to be carried from a well or other source.

Staying fed

Food preparation wasn’t just the cooking. Without refrigeration, any meat needed to be pickled or smoked for longer-term storage. The dairy cows also required milking twice a day, and the milk stored in a cool place. Cream was separated, and butter and cheese needed to be made. (And when done, the ladles, skimmers, milk pans, butter pots, scales, and tubs had to be cleaned and boiled.) Since bread was a key staple, she also had to make bread, usually once or twice a week since it required a large amount of fuel to bake in the wood oven. Daily bread was often a combination of corn meal, rye, and wheat flour. Wheat bread, due to the scarcity of wheat, was often reserved for the best cakes or special meals. Until the end of the 18th century, lightness in the popular baked pies, tarts, and breads could be achieved only by laboriously beating eggs into dough or by adding yeast.

Staying hydrated

Since drinking the water was unhealthy because nobody removed the pathogens, the wife was also responsible for brewing beer and making mead, flower or fruit wines, or hard ciders or perry (pears). (Even children drank low-alcohol beers and ciders.) Women often combined baking with brewing since both required yeast, and brewing produced a new supply.

In her spare time in the evenings, she also needed to gather wool, cotton, or other raw material, spin it into thread, and ultimately create the textiles to clothe the family. If she wanted color in those threads, she also needed to make dyes.

Staying clean

To keep all this clean, she had to collect the tallow for soap making, usually a mixture of tallow and ashes dissolved in water. Even toothpaste was homemade. Here’s a recipe: “a quart of honey, as much vinegar and half as much white wine, boil them together and wash your teeth therewith.” Before electricity and gas, you also needed candles to light the home at night. The simplest candles included a twisted cloth that had to be dipped in fat repeatedly. To make a large number, though, candles were made by pouring the preserved fat into molds in which wicks had been fixed.

But eventually, labor-saving devices began to enter the kitchen. The eggbeater (remember laboriously beating eggs?) was invented in 1857. For food preservation, iceboxes became commonplace in the 1800s, but refrigerators powered by electricity weren’t invented until the mid-1900s. As for stoves, the first cast-iron stove was produced in Lynn, Massachusetts in 1642, and Benjamin Franklin invented his own stove, but it wasn’t until the mid-1800s that kitchen stoves became commonplace.

Ah, progress! These days, I average about an hour a day preparing our main meal. I sure wouldn’t go back to “the good old days.” Happy Fourth of July!

Please click on the headline to view the blog on the website. You can log in and comment at the end of the blog to share your thoughts and start a discussion, or suggest a topic for Farmboy in the Kitchen.

If you’d like to share the blog, click on the Facebook icon or one of the others. Thanks!

One Comment

Tracy May

Man, I get exhausted just reading about it! And I share my Lynn, Massachusetts birthplace with the iron stove? Cool! Who knew? 😁